Precise New Measurements From Hubble Confirm the Accelerating Expansion of the Universe. Still no Idea Why it’s Happening:

In the 1920s, Edwin Hubble made the groundbreaking revelation that the Universe was in a state of expansion. Originally predicted as a consequence of

Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, this confirmation led to what came to be known as

Hubble’s Constant. In the ensuring decades, and thanks to the deployment of next-generation telescopes – like the aptly-named

Hubble Space Telescope (HST) – scientists have been forced to revise this law.

In short, in the past few decades, the ability to see farther into space (and deeper into time) has allowed astronomers to make more accurate measurements about how rapidly the early Universe expanded. And thanks to a

new survey performed using Hubble, an international team of astronomers has been able to conduct the most precise measurements of the expansion rate of the Universe to date.

This survey was conducted by the

Supernova H0 for the Equation of State (SH0ES) team, an international group of astronomers that has been on a quest to refine the accuracy of the Hubble Constant since 2005. The group is led by Adam Reiss of the

Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and

Johns Hopkins University, and includes members from the

American Museum of Natural History, the

Neils Bohr Institute, the

National Optical Astronomy Observatory, and many prestigious universities and research institutions.

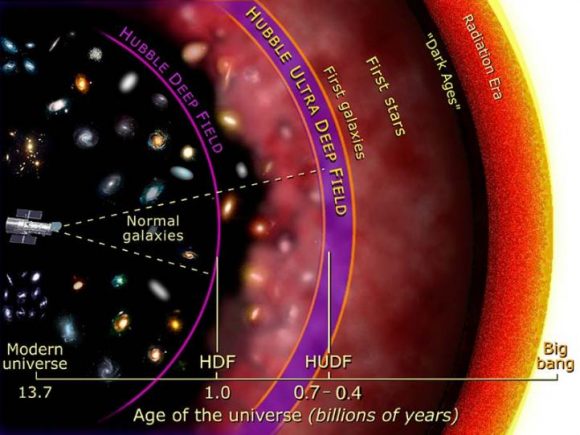

Illustration of the depth by which Hubble imaged galaxies in prior Deep Field initiatives, in units of the Age of the Universe. Credit: NASA and A. Feild (STScI) The study which describes their findings recently appeared in

The Astrophysical Journal under the title “

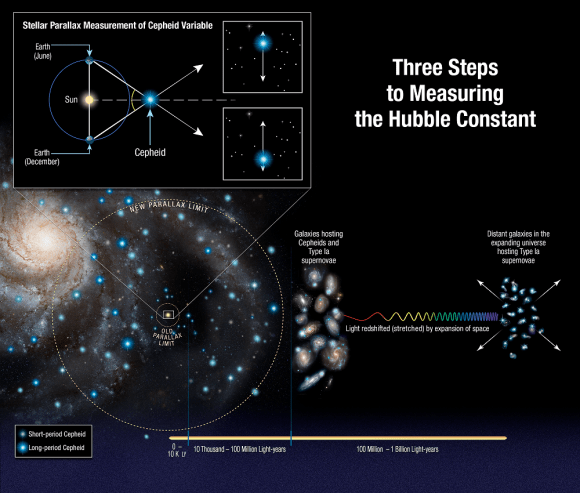

Type Ia Supernova Distances at Redshift >1.5 from the Hubble Space Telescope Multi-cycle Treasury Programs: The Early Expansion Rate“. For the sake of their study, and consistent with their long term goals, the team sought to construct a new and more accurate “distance ladder”.

This tool is how astronomers have traditionally measured distances in the Universe, which consists of relying on distance markers like Cepheid variables – pulsating stars whose distances can be inferred by comparing their intrinsic brightness with their apparent brightness. These measurements are then compared to the way light from distance galaxies is redshifted to determine how fast the space between galaxies is expanding.

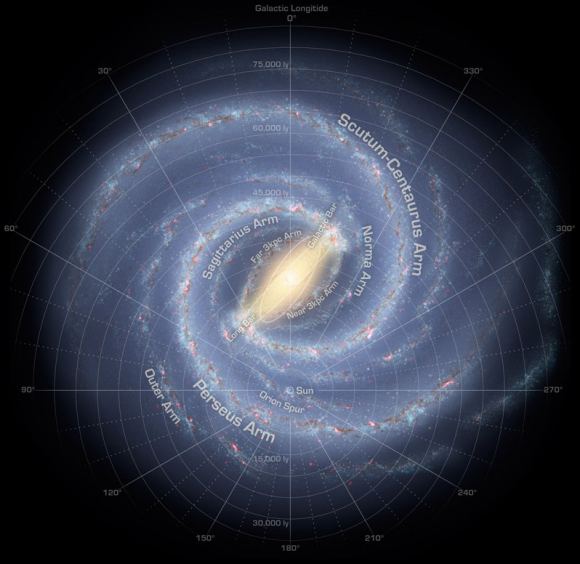

From this, the Hubble Constant is derived. To build their distant ladder, Riess and his team conducted parallax measurements using

Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) of eight newly-analyzed Cepheid variable stars in the Milky Way. These stars are about 10 times farther away than any studied previously – between 6,000 and 12,000 light-year from Earth – and pulsate at longer intervals.

To ensure accuracy that would account for the wobbles of these stars, the team also developed a new method where Hubble would measure a star’s position a thousand times a minute every six months for four years. The team then compared the brightness of these eight stars with more distant Cepheids to ensure that they could calculate the distances to other galaxies with more precision.

Illustration showing three steps astronomers used to measure the universe’s expansion rate (Hubble constant) to an unprecedented accuracy, reducing the total uncertainty to 2.3 percent. Credits: NASA/ESA/A. Feild (STScI)/and A. Riess (STScI/JHU) Using the new technique, Hubble was able to capture the change in position of these stars relative to others, which simplified things immensely. As Riess explained in a NASA

press release:

“This method allows for repeated opportunities to measure the extremely tiny displacements due to parallax. You’re measuring the separation between two stars, not just in one place on the camera, but over and over thousands of times, reducing the errors in measurement.”

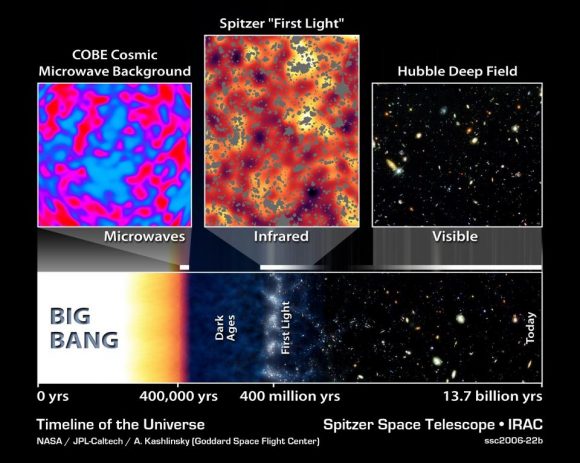

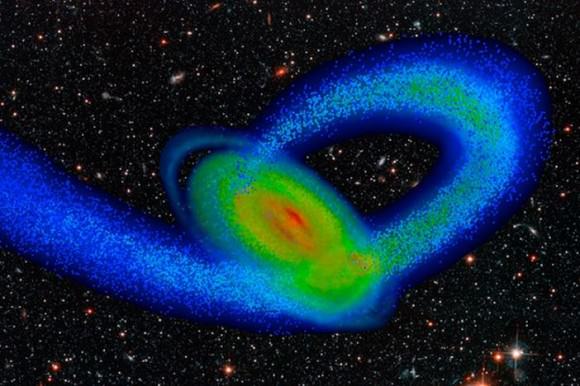

Compared to previous surveys, the team was able to extend the number of stars analyzed to distances up to 10 times farther. However, their results also contradicted those obtained by the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Planck satellite, which has been measuring the

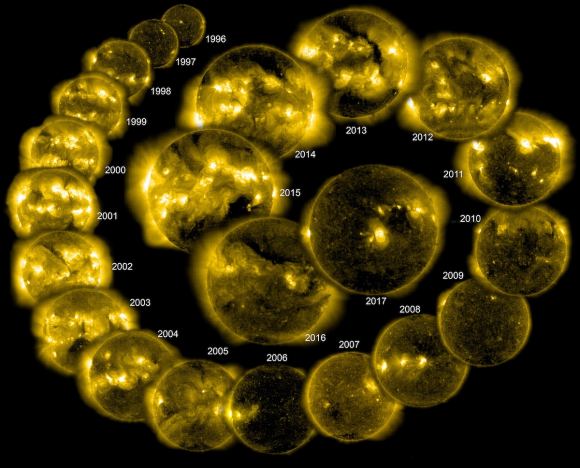

Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) – the leftover radiation created by the Big Bang – since it was deployed in 2009.

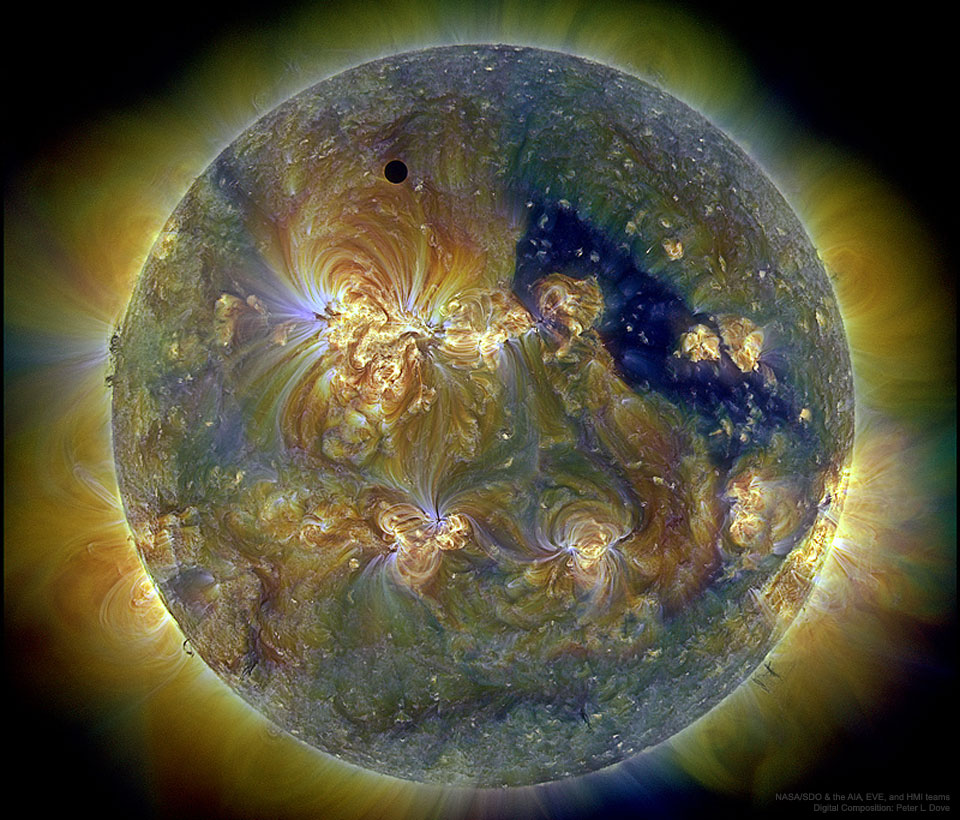

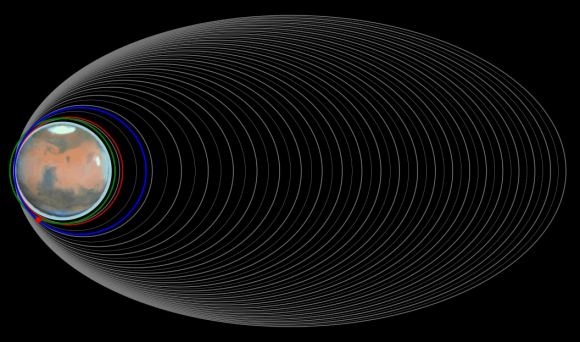

By mapping the CMB, Planck has been able to trace the expansion of the cosmos during the early Universe – circa. 378,000 years after the Big Bang. Planck’s result predicted that the Hubble constant value should now be 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec (3.3 million light-years), and could be no higher than 69 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

The Big Bang timeline of the Universe. Cosmic neutrinos affect the CMB at the time it was emitted, and physics takes care of the rest of their evolution until today. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/A. Kashlinsky (GSFC). Based on their sruvey, Riess’s team obtained a value of 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec, a discrepancy of 9%. Essentially, their results indicate that galaxies are moving at a faster rate than that implied by observations of the early Universe. Because the Hubble data was so precise, astronomers cannot dismiss the gap between the two results as errors in any single measurement or method. As Reiss explained:

“The community is really grappling with understanding the meaning of this discrepancy… Both results have been tested multiple ways, so barring a series of unrelated mistakes. it is increasingly likely that this is not a bug but a feature of the universe.”

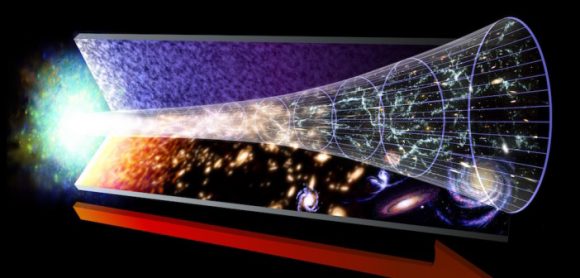

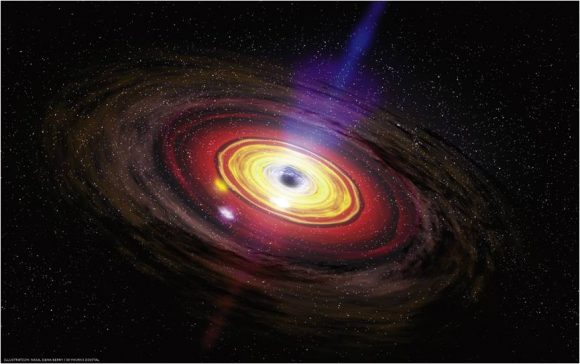

These latest results therefore suggest that some previously unknown force or some new physics might be at work in the Universe. In terms of explanations, Reiss and his team have offered three possibilities, all of which have to do with the 95% of the Universe that we cannot see (i.e. dark matter and dark energy). In 2011, Reiss and two other scientists were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for their 1998 discovery that the Universe was in an accelerated rate of expansion.

Consistent with that, they suggest that Dark Energy could be pushing galaxies apart with increasing strength. Another possibility is that there is an undiscovered subatomic particle out there that is similar to a neutrino, but interacts with normal matter by gravity instead of subatomic forces. These “sterile neutrinos” would travel at close to the speed of light and could collectively be known as “dark radiation”.

This illustration shows the evolution of the Universe, from the Big Bang on the left, to modern times on the right. Credit: NASA Any of these possibilities would mean that the contents of the early Universe were different, thus forcing a rethink of our cosmological models. At present, Riess and colleagues don’t have any answers, but plan to continue fine-tuning their measurements. So far, the SHoES team has decreased the uncertainty of the Hubble Constant to 2.3%.

This is in keeping with one of the central goals of the Hubble Space Telescope, which was to help reduce the uncertainty value in Hubble’s Constant, for which estimates once varied by a factor of 2.

So while this discrepancy opens the door to new and challenging questions, it also reduces our uncertainty substantially when it comes to measuring the Universe. Ultimately, this will improve our understanding of how the Universe evolved after it was created in a fiery cataclysm 13.8 billion years ago.

Further Reading: NASA,

The Astrophysical Journal

The post

Precise New Measurements From Hubble Confirm the Accelerating Expansion of the Universe. Still no Idea Why it’s Happening appeared first on

Universe Today.