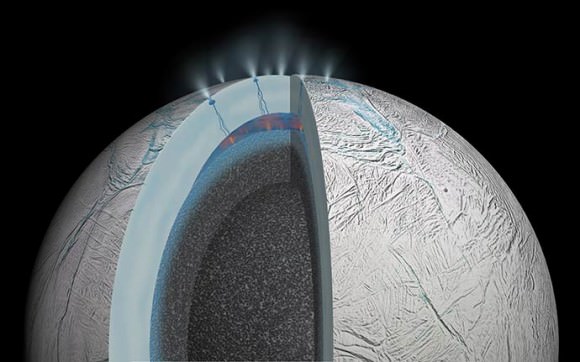

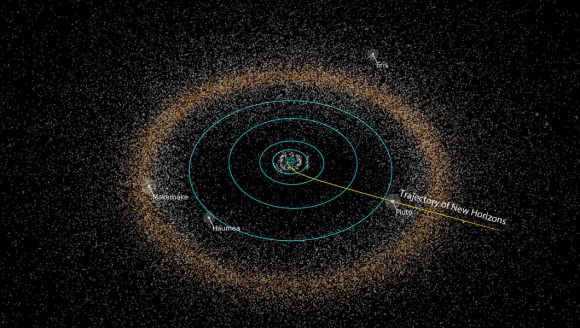

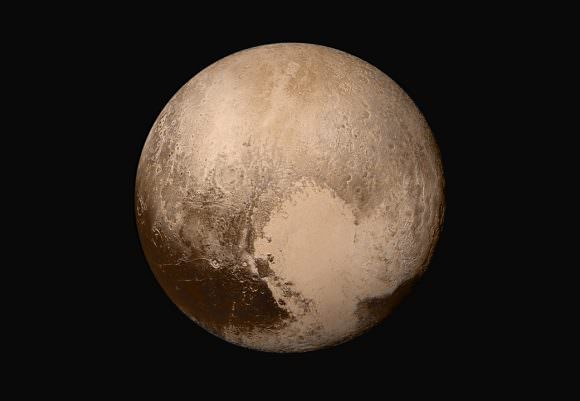

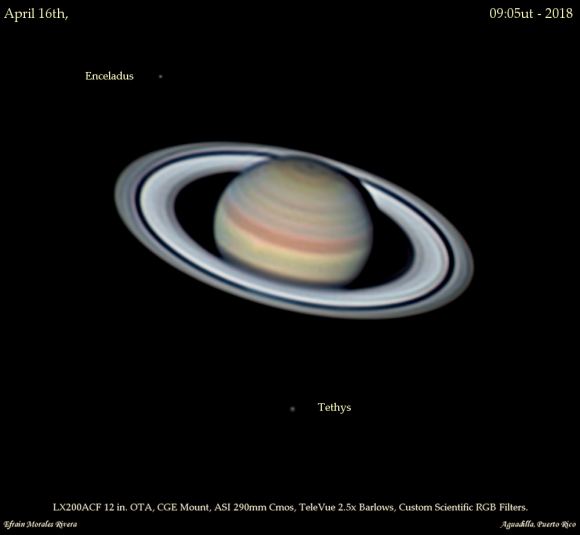

For decades, scientists have believed that there could be life beneath the icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa. Since that time, multiple lines of evidence have emerged that suggest that it is not alone. Indeed, within the Solar System, there are many “ocean worlds” that could potentially host life, including Ceres, Ganymede, Enceladus, Titan, Dione, Triton, and maybe even Pluto.

But what if the elements for life as we know it are not abundant enough on these worlds? In a new study, two researchers from the Harvard Smithsonian Center of Astrophysics (CfA) sought to determine if there could in fact be a scarcity of bioessential elements on ocean worlds. Their conclusions could have wide-ranging implications for the existence of life in the Solar System and beyond, not to mention our ability to study it.

The study, titled “Is extraterrestrial life suppressed on subsurface ocean worlds due to the paucity of bioessential elements?” recently appeared online. The study was led by Manasvi Lingam, a postdoctoral fellow at the Institute for Theory and Computation (ITC) at Harvard University and the CfA, with the support of Abraham Loeb – the director of the ITC and the Frank B. Baird, Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard.

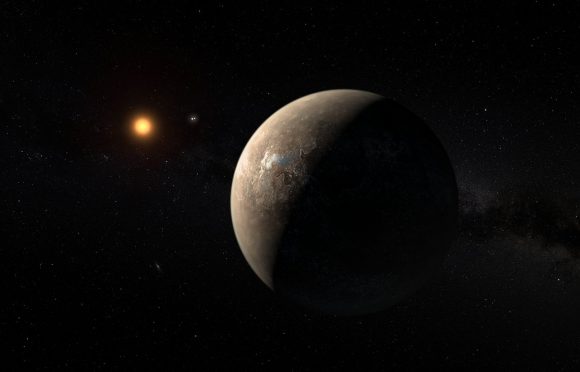

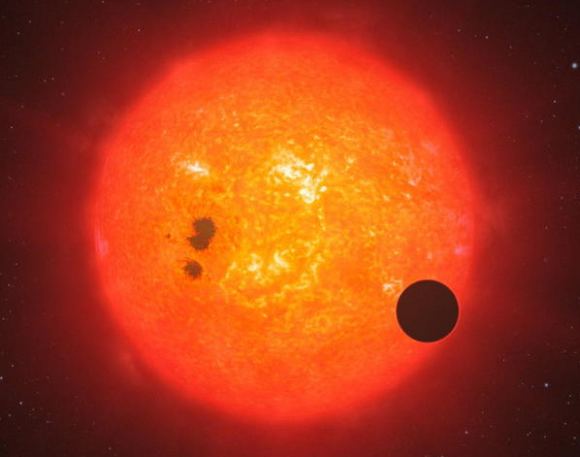

In previous studies, questions on the habitability of moons and other planets have tended to focus on the existence of water. This has been true when it comes to the study of planets and moons within the Solar System, and especially true when it comes the study of extra-solar planets. When they have found new exoplanets, astronomers have paid close attention to whether or not the planet in question orbits within its star’s habitable zone.

This is key to determining whether or not the planet can support liquid water on its surface. In addition, astronomers have attempted to obtain spectra from around rocky exoplanets to determine if water loss is taking place from its atmosphere, as evidenced by the presence of hydrogen gas. Meanwhile, other studies have attempted to determine the presence of energy sources, since this is also essential to life as we know it.

In contrast, Dr. Lingam and Prof. Loeb considered how the existence of life on ocean planets could be dependent on the availability of limiting nutrients (LN). For some time, there has been considerable debate as to which nutrients would be essential to extra-terrestrial life, since these elements could vary from place to place and over timescales. As Lingam told Universe Today via email:

“The mostly commonly accepted list of elements necessary for life as we know it comprises of hydrogen, oxygen, carbon, nitrogen and sulphur. In addition, certain trace metals (e.g. iron and molybdenum) may also be valuable for life as we know it, but the list of bioessential trace metals is subject to a higher degree of uncertainty and variability.”

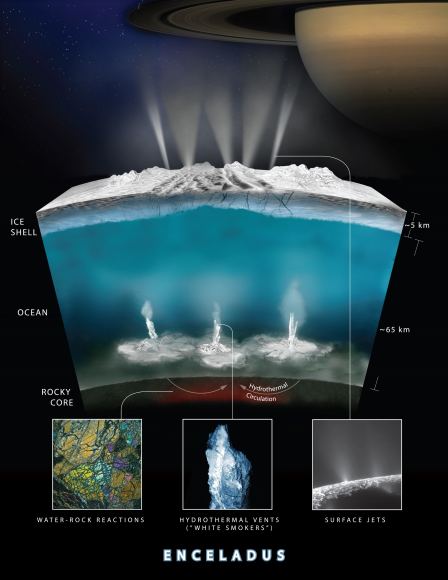

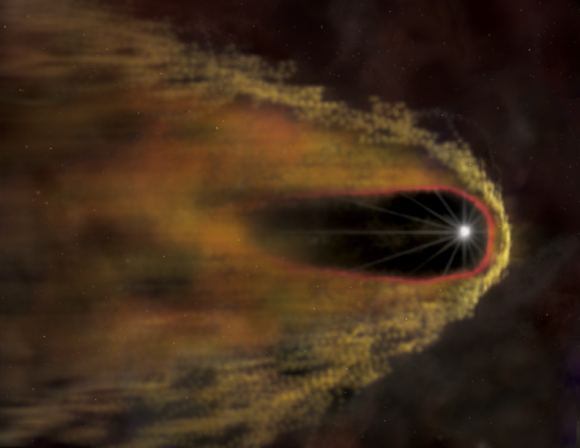

Artist rendering showing an interior cross-section of the crust of Enceladus, which shows how hydrothermal activity may be causing the plumes of water at the moon’s surface. Credits: NASA-GSFC/SVS, NASA/JPL-Caltech/Southwest Research Institute

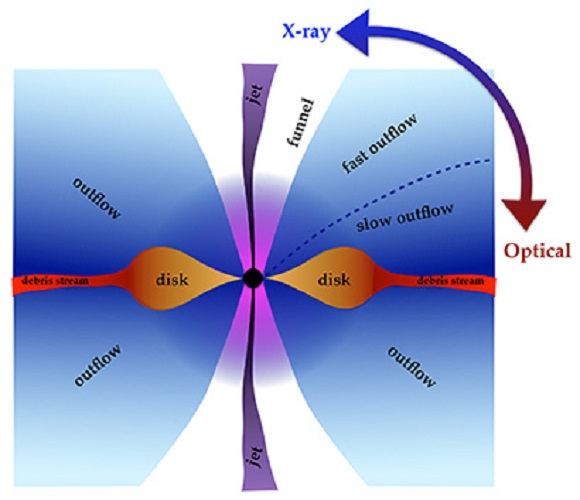

Of these nutrients, they determined that the most important would be phosphorus, and examined how abundant this and other elements could be on ocean worlds, where conditions as vastly different. As Dr. Lingam explained, it is reasonable to assume that on these worlds, the potential existence of life would also come down to a balance between the net inflow (sources) and net outflow (sinks).

“If the sinks are much more dominant than the sources, it could indicate that the elements would be depleted relatively quickly. In other to estimate the magnitudes of the sources and sinks, we drew upon our knowledge of the Earth and coupled it with other basic parameters of these ocean worlds such as the pH of the ocean, the size of the world, etc. known from observations/theoretical models.”

While atmospheric sources would not be available to interior oceans, Dr. Lingam and Prof. Loeb considered the contribution played by hydrothermal vents. Already, there is abundant evidence that these exist on Europa, Enceladus, and other ocean worlds. They also considered abiotic sources, which consist of minerals leached from rocks by rain on Earth, but would consist of the weathering of rocks by these moons’ interior oceans.

Artist’s rendering of possible hydrothermal activity that may be taking place on and under the seafloor of Enceladus. Credit: NASA/JPL

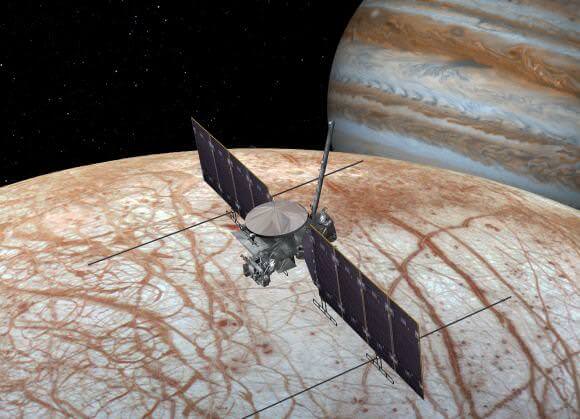

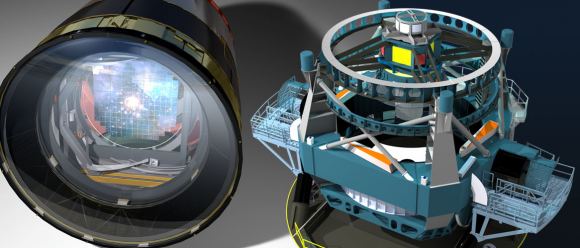

“We found that, as per the assumptions in our model, phosphorus, which is one of the bioessential elements, is depleted over fast timescales (by geological standards) on ocean worlds whose oceans are neutral or alkaline in nature, and which possess hydrothermal activity (i.e. hydrothermal vent systems at the ocean floor). Hence, our work suggests that life may exist in low concentrations globally in these ocean worlds (or be present only in local patches), and may therefore not be easily detectable.”This naturally has implications for missions destined for Europa and other moons in the outer Solar System. These include the NASA Europa Clipper mission, which is currently scheduled to launch between 2022 and 2025. Through a series of flybys of Europa, this probe will attempt to measure biomarkers in the plume activity coming from the moon’s surface.

Similar missions have been proposed for Enceladus, and NASA is also considering a “Dragonfly” mission to explore Titan’s atmosphere, surface and methane lakes. However, if Dr. Lingam and Prof. Loeb’s study is correct, then the chances of these missions finding any signs of life on an ocean world in the Solar System are rather slim. Nevertheless, as Lingam indicated, they still believe that such missions should be mounted.

“Although our model predicts that future space missions to these worlds might have low chances of success in terms of detecting extraterrestrial life, we believe that such missions are still worthy of being pursued,” he said. “This is because they will offer an excellent opportunity to: (i) test and/or falsify the key predictions of our model, and (ii) collect more data and improve our understanding of ocean worlds and their biogeochemical cycles.”

In addition, as Prof. Loeb indicated via email, this study was focused on “life as we know it”. If a mission to these worlds did find sources of extra-terrestrial life, then it would indicate that life can arise from conditions and elements that we are not familiar with. As such, the exploration of Europa and other ocean worlds is not only advisable, but necessary.

“Our paper shows that elements that are essential for the ‘chemistry-of-life-as-we-know-it’, such as phosphorous, are depleted in subsurface oceans,” he said. “As a result, life would be challenging in the oceans suspected to exist under the surface ice of Europa or Enceladus. If future missions confirm the depleted level of phosphorous but nevertheless find life in these oceans, then we would know of a new chemical path for life other than the one on Earth.”

In the end, scientists are forced to take the “low-hanging fruit” approach when it comes to searching for life in the Universe . Until such time that we find life beyond Earth, all of our educated guesses will be based on life as it exists here. I can’t imagine a better reason to get out there and explore the Universe than this!

Further Reading: arXiv

The post Are There Enough Chemicals on Icy Worlds to Support Life? appeared first on Universe Today.