There’s a supermassive black hole at the center of almost every galaxy in the Universe. How did they get there? What’s the relationship between these monster black holes and the galaxies that surround them?

Every time astronomers look farther out in the Universe, they discover new mysteries. These mysteries require all new tools and techniques to understand. These mysteries lead to more mysteries. What I’m saying is that it’s mystery turtles all the way down.

One of the most fascinating is the discovery of quasars, understanding what they are, and the unveiling of an even deeper mystery, where do they come from?

As always, I’m getting ahead of myself, so first, let’s go back and talk about the discovery of quasars.

The astronomer Hong-Yee Chiu coined the term “quasar”, which stood for quasi-stellar object. They were like stars, shining from a single point source, but they clearly weren’t stars, blazing with more radiation than an entire galaxy.

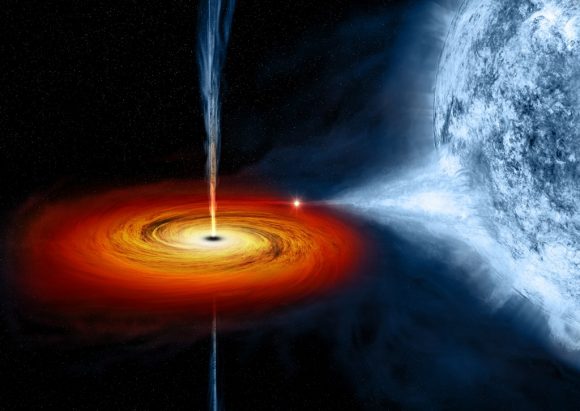

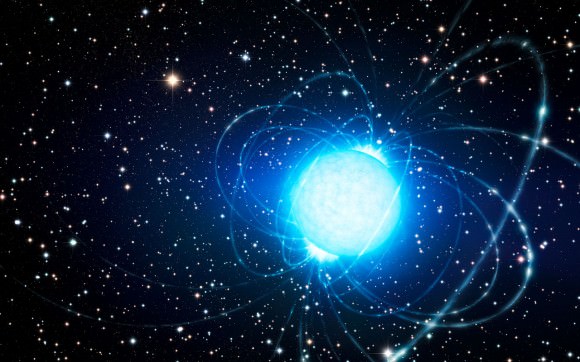

Over the decades, astronomers puzzled out the nature of quasars, learning that they were actually black holes, actively feeding and blasting out radiation, visible billions of light-years away.

But they weren’t the stellar mass black holes, which were known to be from the death of giant stars. These were supermassive black holes, with millions or even billions of times the mass of the Sun.

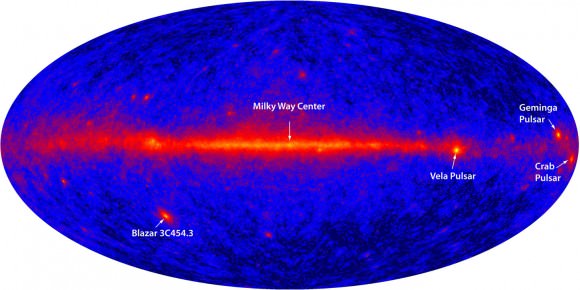

As far back as the 1970s, astronomers considered the possibility that there might be these supermassive black holes at the heart of many other galaxies, even the Milky Way.

This would match the emissions of a supermassive black hole that wasn’t actively feeding on material. Our own galaxy could have been a quasar in the past, or in the future, but right now, the black hole was mostly silent, apart from this subtle radiation.

Astronomers needed to be certain, so they performed a detailed survey of the very center of the Milky Way in the infrared spectrum, which allowed them to see through the gas and dust that obscures the core in visible light.

They discovered a group of stars orbiting Sagittarius A-star, like comets orbiting the Sun. Only a black hole with millions of times the mass of the Sun could provide the kind of gravitational anchor to whip these stars around in such bizarre orbits.

Further surveys found a supermassive black hole at the heart of the Andromeda Galaxy, in fact, it appears as if these monsters are at the center of almost every galaxy in the Universe.

But how did they form? Where did they come from? Did the galaxy form first, and cause the black hole to form at the middle, or did the black hole form, and build up a galaxy around them?

Until recently, this was actually still one of the big unsolved mysteries in astronomy. That said, astronomers have done plenty of research, using more and more sensitive observatories, worked out their theories, and now they’re gathering evidence to help get to the bottom of this mystery.

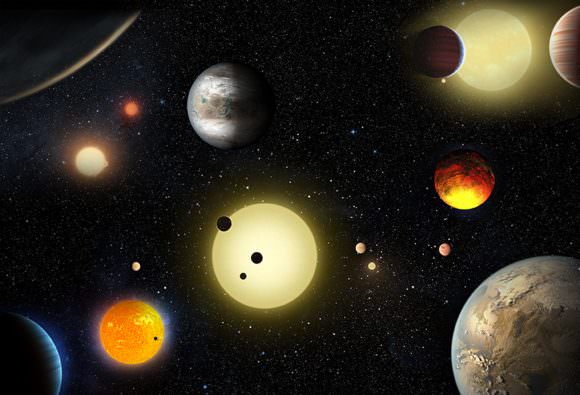

Astronomers have developed two models for how the large scale structure of the Universe came together: top down and bottom up.

In the top down model, an entire galactic supercluster formed all at once out of a huge cloud of primordial hydrogen left over from the Big Bang. A supercluster’s worth of stars.

As the cloud came together it, it spun up, kicking out smaller spirals and dwarf galaxies. These could have combined later on to form the more complex structure we see today. The supermassive black holes would have formed as the dense cores of these galaxies as they came together.

That’s top down. One big event that leads to the structure we see today.

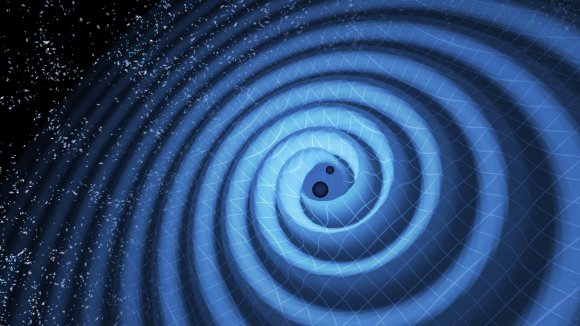

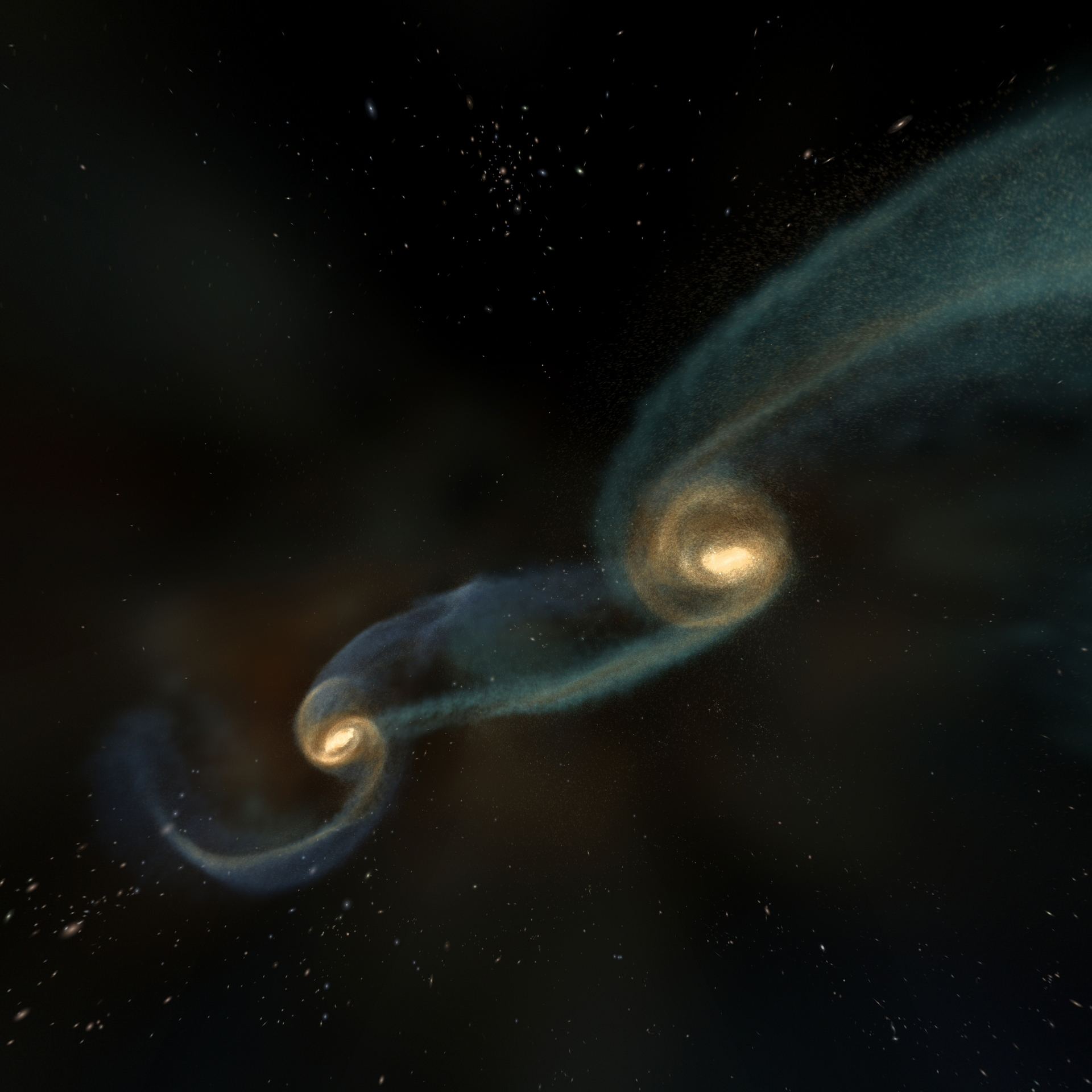

In the bottom up model, pockets of gas and dust collected together into larger and larger masses, eventually forming dwarf galaxies, and even the clusters and superclusters we see today. The supermassive black holes at the heart of galaxies were grown from collisions and mergers between black holes over eons.

In fact, this is actually how astronomers think the planets in the Solar System formed. By pieces of dust attracting one another into larger and larger grains until the planet-sized objects formed over millions of years.

Bottom up, small parts coming together.

Shortly after the Big Bang, the entire Universe was incredibly dense. But it wasn’t the same density everywhere. Tiny quantum fluctuations in density at the beginning evolved over billions of years of expansion into the galactic superclusters we see today.

I want to stop and let this sink into your brain for a second. There were microscopic variations in density in the early Universe. And these variations became the structures hundreds of millions of light-years across we see today.

Imagine the two forces at play as the expansion of the Universe happened. On the one hand, you’ve got the mutual gravity of the particles pulling one another together. And on the other hand, you’ve got the expansion of the Universe separating the particles from one another. The size of the galaxies, clusters and superclusters were decided by the balance point of those opposing forces.

If small pieces came together, then you’d get that bottom up formation. If large pieces came together, you’d get that top down formation.

When astronomers look out into the Universe at the largest scales, they observe clusters and superclusters as far as they can see – which supports the top down model.

On the other hand, observations show that the first stars formed just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang, which supports bottom up.

So the answer is both?

No, the most modern observations give the edge to the bottom up processes.

The key is that gravity moves at the speed of light, which means that the gravitational interactions between particles spreading away from each other needed to catch up, going the speed of light.

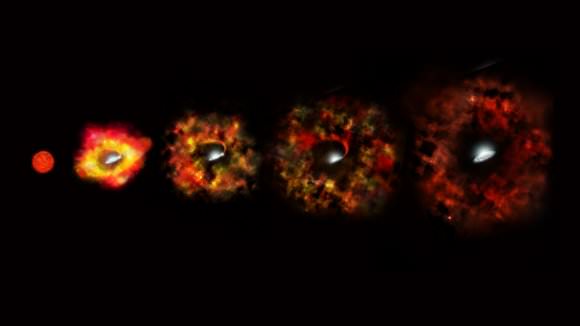

In other words, you wouldn’t get a supercluster’s worth of material coming together, only a star’s worth of material. But these first stars were made of pure hydrogen and helium, and could grow much more massive than the stars we have today. They would live fast and die in supernova explosions, creating much more massive black holes than we get today.

There was a recent observation that supports this conclusion. Earlier this year, astronomers announced the discovery of supermassive black holes at the center of relatively tiny galaxies. In our own Milky Way, the supermassive black hole is 4.1 million times the mass of the Sun, but accounts for only .01% of the galaxy’s total mass.

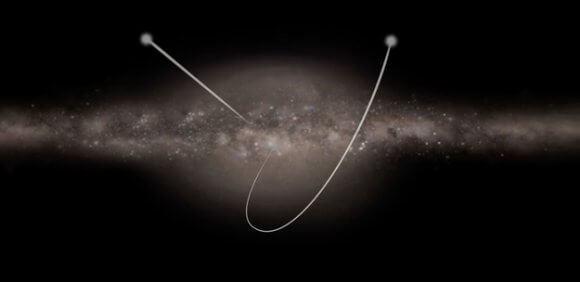

But astronomers from the University of Utah found two ultra compact galaxies with black holes of 4.4 million and 5.8 million times the mass of the Sun respectively. And yet, the black holes account for 13 and 18 percent of the mass of their host galaxies.

The thinking is that these galaxies were once normal, but collided with other galaxies earlier on in the history of the Universe, were stripped of their stars and then were spat out to roam the cosmos.

They’re the victims of those early merging events, evidence of the carnage that happened in the early Universe when the mergers were happening.

We always talk about the unsolved mysteries in the Universe, but this is one that astronomers are starting to puzzle out.

It seems most likely that the structure of the Universe we see today formed bottom up. The first stars came together into protogalaxies, dying as supernova to form the first black holes. The structure of the Universe we see today is the end result of billions of years of formation and destruction. With the supermassive black holes coming together over time.

Once telescopes like James Webb get to work, we should be able to see these pieces coming together, at the very edge of the observable Universe.

The post Supermassive Black Holes or Their Galaxies? Which Came First? appeared first on Universe Today.

| Original enclosures: |

| 322SupermassiveBlackHolesOrGalaxies.mp4 |