Mars Express Captures Mars’ Moving Bow Shock:

Every planet in our Solar System interacts with the stream of energetic particles coming from our Sun. Often referred to as “solar wind”, these particles consist mainly of electrons, protons and alpha particles that are constantly making their way towards interstellar space. Where this stream comes into contact with a planet’s magnetosphere or atmosphere, it forms a region around them known as a “bow shock”.

These regions form in front of the planet, slowing and diverting solar wind as it moves past – much like how water is diverted around a boat. In the case of

Mars, it is the planet’s ionosphere that provides the conductive environment necessary for a bow shock to form. And according to a

new study by a team of European scientists, Mars’ bow shock shifts as a result of changes in the planet’s atmosphere.

The study, titled “

Annual Variations in the Martian Bow Shock Location as Observed by the Mars Express Mission“, appeared in the

Journal of Geophysical Letters: Space Physics. Using data from the

Mars Express orbiter, the science team sought to investigate how and why the bow shock’s location varies during the course of several Martian years, and what factors are chiefly be responsible.

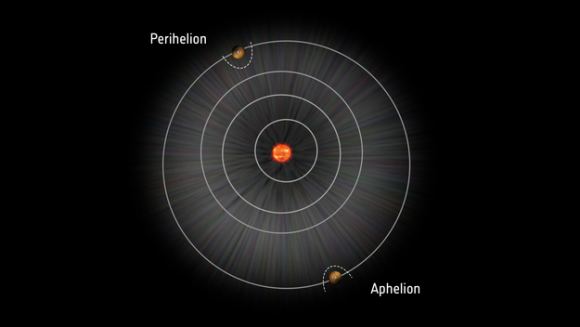

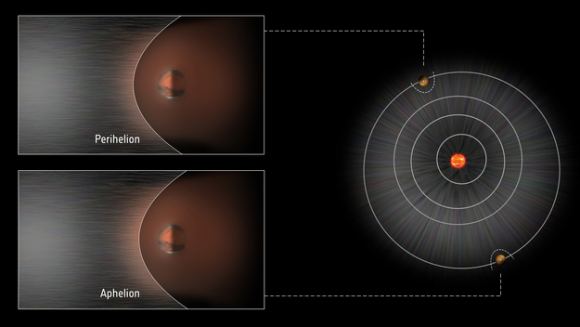

Diagram of Mars’ orbit and changes to its bow shock between perihelion and aphelion. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab For many decades, astronomers have been aware that bow shocks form upstream of a planet, where interaction between solar wind and the planet causes energetic particles to slow down and gradually be diverted. Where the solar wind meets the planet’s magnetosphere or atmosphere, a sharp boundary line is formed, which them extends around the planet in a widening arc.

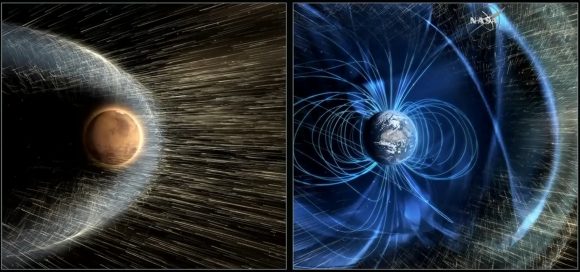

This is where the term bow shock comes from, owing to its distinctive shape. In the case of Mars, which does not have a global magnetic field and a rather thin atmosphere to boot (less than 1% of Earth’s atmospheric pressure at sea level), it is the electrically-charged region of the upper atmosphere (the ionosphere) that is responsible for creating the bow shock around the planet.

At the same time, Mars relatively small size, mass and gravity allows for the formation of an extended atmosphere (i.e. an exosphere). In this portion of Mars’ atmosphere, gaseous atoms and molecules escape into space and interact directly with solar wind. Over the years, this extended atmosphere and Mars’ bow shock have been observed by multiple orbiter missions, which have detected variations in the latter’s boundary.

This is believed to be caused by multiple factors, not the least of which is distance. Because Mars has an relatively eccentric orbit (0.0934 compared to Earth’s 0.0167), its distance from the Sun varies quite a bit – going from 206.7 million km (128.437 million mi; 1.3814 AU) at perihelion to 249.2 million km (154.8457 million mi; 1.666 AU) at aphelion.

Illustration showing how Mars and Earth interact with solar wind. Credit: NASA When the planet is closer, the dynamic pressure of the solar wind against its atmosphere increases. However, this change in distance also coincides with increases in the amount of incoming extreme ultraviolet (EUV) solar radiation. As a result, the rate at which ions and electrons (aka. plasma) are produced in the upper atmosphere increases, causing increased thermal pressure that counteracts the incoming solar wind.

Newly-created ions within the extended atmosphere are also picked up and accelerated by the electromagnetic fields being carried by the solar wind. This has the effect of slowing it down and causing Mars’ bowshock to shift its position. All of this has been known to happen over the course of a single

Martian year – which is equivalent to 686.971 Earth days or 668.5991 Martian days (sols).

However, how it behaves over longer periods of time is a question that was previously unanswered. As such, the team of European scientists consulted data obtained by the

Mars Express mission over a five year period. This data was taken by the

Analyser of Space Plasma and EneRgetic Atoms (ASPERA-3) Electron Spectrometer (ELS), which the team used to examine a total of 11,861 bow shock crossings.

What they found was that, on average, the bow shock is closer to Mars when it is near aphelion (8102 km), and further away at perihelion (8984 km). This works out to a variation of about 11% during the Martian year, which is pretty consistent with its eccentricity. However, the team wanted to see which (if any) of the previously-studied mechanisms was chiefly responsible for this change.

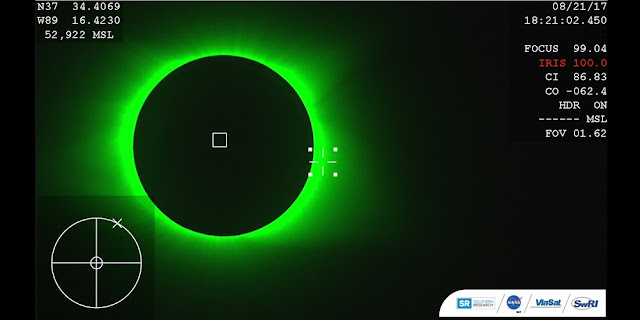

The moving Martian bow shock. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab Towards this end, the team considered variations in solar wind density, the strength of the interplanetary magnetic field, and solar irradiation as primary causes – are all of which decline as the planet gets farther away from the Sun. However, what they found was that the bow shock’s location appeared more sensitive to variations in the Sun’s output of extreme UV radiation rather than to variations in solar wind itself.

The variations in bow shock distance also appeared to be related to the amount of dust in the Martian atmosphere. This increases as Mars approaches perihelion, causing the atmosphere to absorb more solar radiation and heat up. Much like how increased levels of EUV leads to an increased amount of plasma in the ionosphere and exosphere, increased amounts of dust appear to act as a buffer against solar wind.

As Benjamin Hall, a researcher at Lancaster University in the UK and the lead author of the paper, said in an ESA

press release:

“Dust storms have been previously shown to interact with the upper atmosphere and ionosphere of Mars, so there may be an indirect coupling between the dust storms and bow shock location… However, we do not draw any further conclusions on how the dust storms could directly impact the location of the Martian bow shock and leave such an investigation to a future study.”

In the end, Hall and his team could not single out any one factor when addressing why Mars’ bow shock shifts over longer periods of time. “It seems likely that no single mechanism can explain our observations, but rather a combined effect of all of them,” he

said. “At this point none of them can be excluded.”

Looking ahead, Hall and his colleagues hope that future missions will help shed additional light on the mechanisms behind Mars shifting bowshock. As Hall indicated, this will likely involve “”joint investigations by ESA’s

Mars Express and

Trace Gas Orbiter, and NASA’s

MAVEN mission. Early data from MAVEN seems to confirm the trends that we discovered.”

While this is not the first analysis that sought to understand how Mars’ atmosphere interacts with solar wind, this particular analysis was based on data obtained over a much longer period of time than any previously study. In the end, the multiple missions that are currently studying Mars are revealing much about the atmospheric dynamics of this planet. A planet which, unlike Earth, has a very weak magnetic field.

What we learn in the process will go a long way towards ensuring that future exploration missions to Mars and other planets that have weak magnetic fields (like Venus and Mercury) are safe and effective. It might even assist us with the creation of permanent bases on these worlds someday!

Further Reading: ESA,

Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics

The post

Mars Express Captures Mars’ Moving Bow Shock appeared first on

Universe Today.