Between the planets of the inner and outer Solar System, there are some stark differences. The planets that resides closer to the Sun are terrestrial (i.e. rocky) in nature, meaning that they are composed of silicate minerals and metals. Beyond the Asteroid Belt, however, the planets are predominantly composed of gases, and are much larger than their terrestrial peers.

This is why astronomers use the term “gas giants” when referring to the planets of the outer Solar System. The more we’ve come to know about these four planets, the more we’ve come to understand that no two gas giants are exactly alike. In addition, ongoing studies of planets beyond our Solar System (aka. “extra-solar planets“) has shown that there are many types of gas giants that do not conform to Solar examples. So what exactly is a “gas giant”?

Definition and Classification:

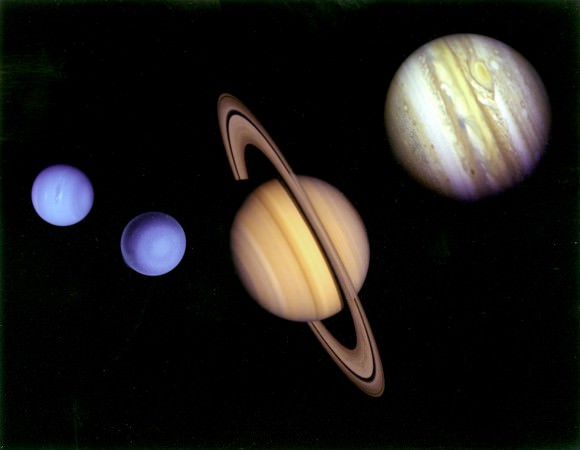

By definition, a gas giant is a planet that is primarily composed of hydrogen and helium. The name was originally coined in 1952 by James Blish, a science fiction writer who used the term to refer to all giant planets. In truth, the term is something of a misnomer, since these elements largely take a liquid and solid form within a gas giant, as a result of the extreme pressure conditions that exist within the interior.The four gas giants of the Solar System (from right to left): Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. Credit: NASA/JPL

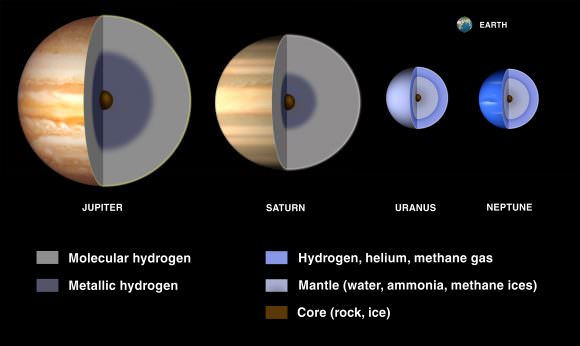

Hence the difference between Jupiter and Saturn on the one and, and Uranus and Neptune on the other. Due to the high concentrations of volatiles (such as water, methane and ammonia) within the latter two – which planetary scientists classify as “ices” – these two giant planets are often called “ice giants”. But since they are composed mainly of hydrogen and helium, they are still considered gas giants alongside Jupiter and Saturn.

Classification:

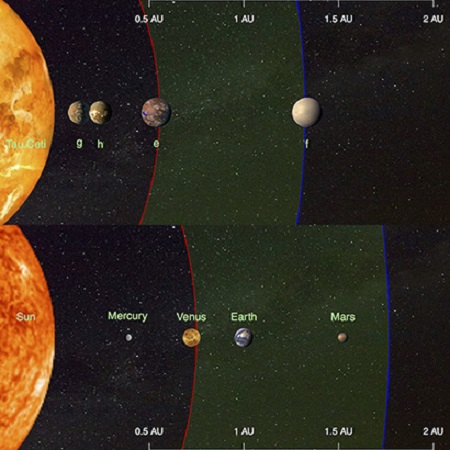

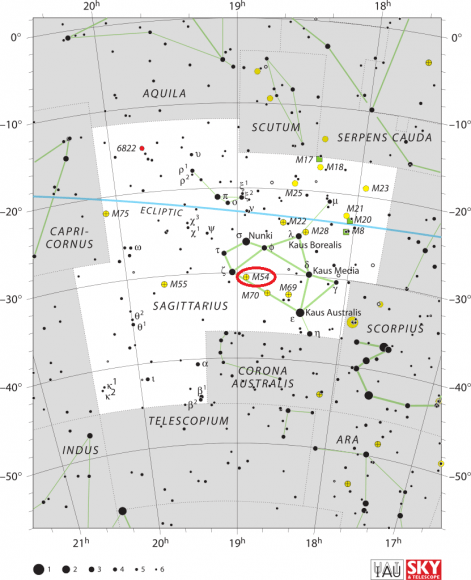

Today, Gas giants are divided into five classes, based on the classification scheme proposed by David Sudarki (et al.) in a 2000 study. Titled “Albedo and Reflection Spectra of Extrasolar Giant Planets“, Sudarsky and his colleagues designated five different types of gas giant based on their appearances and albedo, and how this is affected by their respective distances from their star.Class I: Ammonia Clouds – this class applies to gas giants whose appearances are dominated by ammonia clouds, and which are found in the outer regions of a planetary system. In other words, it applies only to planets that are beyond the “Frost Line”, the distance in a solar nebula from the central protostar where volatile compounds – i.e. water, ammonia, methane, carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide – condense into solid ice grains.

These cutaways illustrate interior models of the giant planets. Jupiter is shown with a rocky core overlaid by a deep layer of metallic hydrogen. Credit: NASA/JPL

Class III: Cloudless – this class applies to gas giants that are generally warmer – 350 K (80 °C; 170 °F) to 800 K ( 530 °C; 980 °F) – and do not form cloud cover because they lack the necessary chemicals. These planets have low albedos since they do not reflect as much light into space. These bodies would also appear like clear blue globes because of the way methane in their atmospheres absorbs light (like Uranus and Neptune).

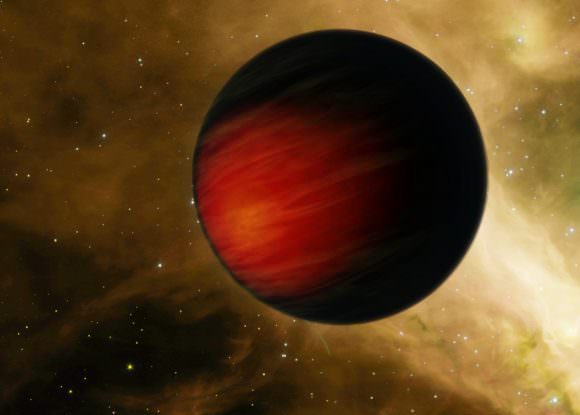

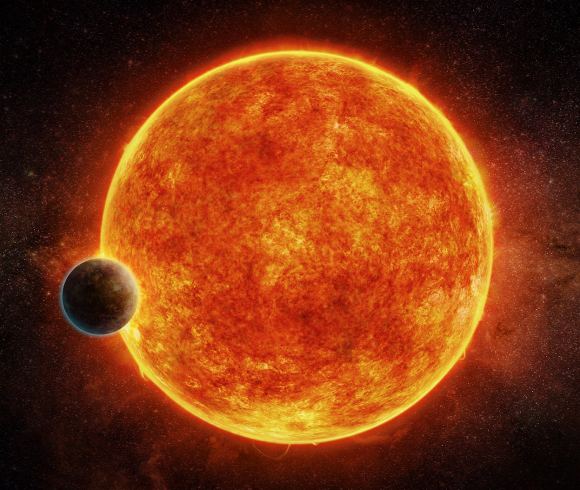

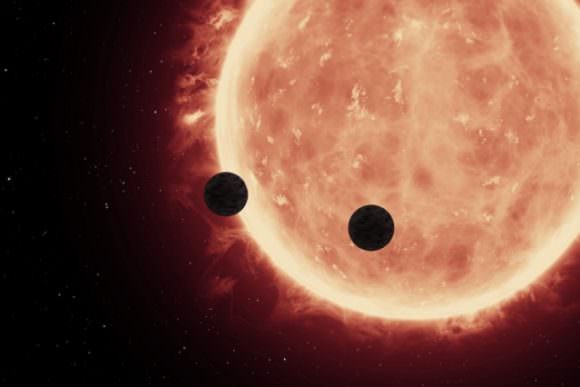

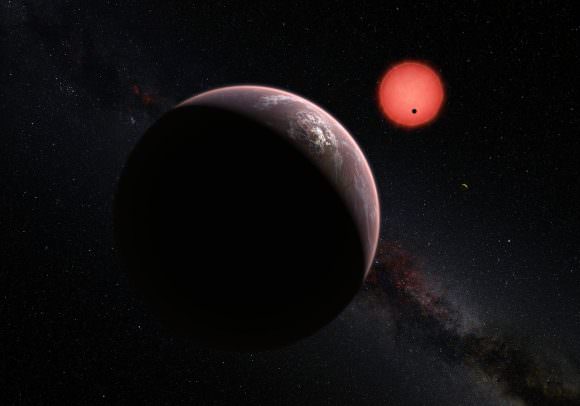

Class IV: Alkali Metals – this class of planets experience temperatures in excess of 900 K (627 °C; 1160 °F), at which point Carbon Monoxide becomes the dominant carbon-carrying molecule in their atmospheres (rather than methane). The abundance of alkali metals also increases substantially, and cloud decks of silicates and metals form deep in their atmospheres. Planets belonging to Class IV and V are referred to as “Hot Jupiters”.

Class V: Silicate Clouds – this applies to the hottest of gas giants, with temperatures above 1400 K (1100 °C; 2100 °F), or cooler planets with lower gravity than Jupiter. For these gas giants, the silicate and iron cloud decks are believed to be high up in the atmosphere. In the case of the former, such gas giants are likely to glow red from thermal radiation and reflected light.

Artist’s concept of “hot Jupiter” exoplanet, a gas giant that orbits very close to its star. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Exoplanets:

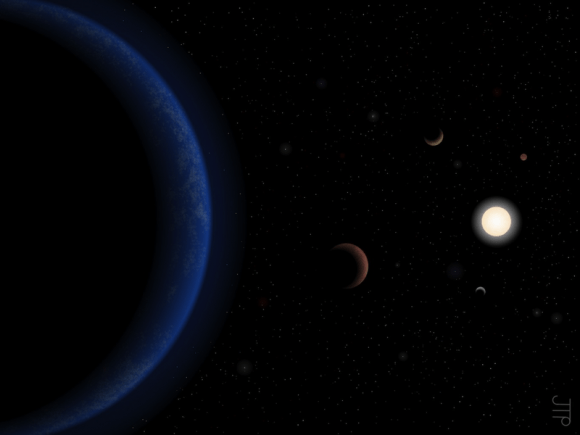

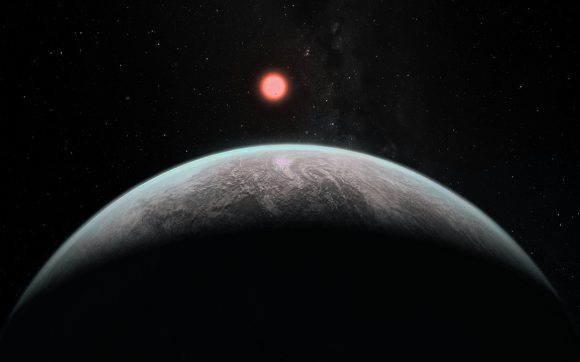

The study of exoplanets has also revealed a wealth of other types of gas giants that are more massive than the Solar counterparts (aka. Super-Jupiters) as well as many that are comparable in size. Other discoveries have been a fraction of the size of their solar counterparts, while some have been so massive that they are just shy of becoming a star. However, given their distance from Earth, their spectra and albedo have cannot always be accurately measured.As such, exoplanet-hunters tend to designate extra-solar gas giants based on their apparent sizes and distances from their stars. In the case of the former, they are often referred to as “Super-Jupiters”, Jupiter-sized, and Neptune-sized. To date, these types of exoplanet account for the majority of discoveries made by Kepler and other missions, since their larger sizes and greater distances from their stars makes them the easiest to detect.

In terms of their respective distances from their sun, exoplanet-hunters divide extra-solar gas giants into two categories: “cold gas giants” and “hot Jupiters”. Typically, cold hydrogen-rich gas giants are more massive than Jupiter but less than about 1.6 Jupiter masses, and will only be slightly larger in volume than Jupiter. For masses above this, gravity will cause the planets to shrink.

Exoplanet surveys have also turned up a class of planet known as “gas dwarfs”, which applies to hydrogen planets that are not as large as the gas giants of the Solar System. These stars have been observed to orbit close to their respective stars, causing them to lose atmospheric mass faster than planets that orbit at greater distances.

For gas giants that occupy the mass range between 13 to 75-80 Jupiter masses, the term “brown dwarf” is used. This designation is reserved for the largest of planetary/substellar objects; in other words, objects that are incredibly large, but not quite massive enough to undergo nuclear fusion in their core and become a star. Below this range are sub-brown dwarfs, while anything above are known as the lightest red dwarf (M9 V) stars.

Like all things astronomical in nature, gas giants are diverse, complex, and immensely fascinating. Between missions that seek to examine the gas giants of our Solar System directly to increasingly sophisticated surveys of distant planets, our knowledge of these mysterious objects continues to grow. And with that, so is our understanding of how star systems form and evolve.

We have written many interesting articles about gas giants here at Universe Today. Here’s The Planet Jupiter, The Planet Saturn, The Planet Uranus, The Planet Neptune, What are the Jovian Planets?, What are the Outer Planets of the Solar System?, What’s Inside a Gas Giant?, and Which Planets Have Rings?

For more information, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration.

Astronomy Cast also has some great episodes on the subject. Here’s Episode 56: Jupiter to get you started!

Sources:

- NASA – Solar System Exploration: Planets

- NASA – Gas Giant Interiors

- Space Facts – Gas Giants

- Wikipedia – Gas Giants

- The Planets – Gas Giants